‘2001: A Space Odyssey,’ 50 Years Later

It was 50 years ago the sci-fi epic “2001: A Space Odyssey” by author Arthur C. Clarke and filmmaker Stanley Kubrick, opened in theaters across America to mixed reviews. The almost three-hour long film, was too cerebral and slow-moving to be appreciated by general audiences in 1968. Today, half a century later, the movie is one of the American Film Institute’s top 100 films of all time.

Film director Douglas Trumbull was a special photographic effects supervisor on the “2001” set. He describes Kubrick as a perfectionist and an innovative genius, who spent four years producing the film.

“He started out with the intention of making a more conventional movie, with dialogue and suspense and character development and drama and things that movies are normally are made out of. And during the production he began stripping away all of the conventions of normal melodrama because he was working on this 70mm giant widescreen Cinerama process and the movie progressively became more immersive. And the more immersive it became and the more experiential it became the less you had to talk about it,” says Trumbull.

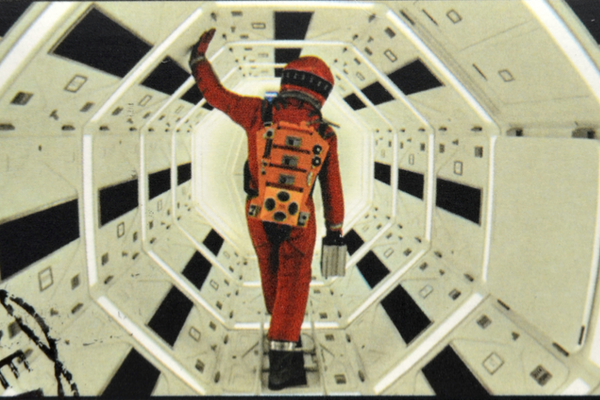

To create this immersive experience Kubrick built “a centrifuge set, the big center piece of the movie” as Trumbull describes it.

The cameras were tied on the rotating set and were filming in 360 degrees. This is how Kubrick created the illusion of the spacecraft crew walking from the floor to the ceiling. And then there was the music.

“The movie differentiates itself in many ways with using classical music rather than a score which underscores every moment and the composer will often gouge the strings at the moment you are supposed to be afraid. Kubrick did not want any of that manipulation,” says Trumbull.

The music of Johann Strauss’ Blue Danube Waltz is in step with Kubrick’s crisp, slow moving images of space: an otherworldly spectacle watched on huge Cinerama curved screens in 1968.

Many describe the effect as ‘hypnotic,’ enhancing the message of “2001:A Space Odyssey,” that humanity’s intellectual advancement was aided by alien intelligence.

Kubrick steered clear of images of stereotypical aliens. Instead, the alien presence appears suddenly, through a looming black monolith, transmitting signals that teach apelike anthropoids how to use tools for hunting and survival. Millions of years later, in Kubrick’s imagined high tech world of 2001, the aliens make contact again through the monolith.

This time, the sleek rectangle prods humans towards an exploration voyage to Jupiter.

“And they get to Jupiter and that’s where the transformation takes place.” By “transformation,” Trumbull means the evolution of Dave Bowman, the only surviving astronaut aboard Spacecraft Discovery 1, into a noncorporeal entity after he makes contact with aliens through a stargate that transcends time and space. Trumbull, takes credit for the visual effects that created the famous Stargate.

“I seemed to be able to come at it with some new solutions for Stanley that no one had thought out before and he began to trust me. So, I would go to him and say ‘I think I have the solution for the Stargate,’ for example, that was one of the high points for me on the movie. And it was this idea that you could take photography and open the camera shutter for a long period of time, several seconds, and move lights and blink them on and off in patterns and create three dimensional light streams for the star gate, which seems to me to be in perfect harmony with the idea of the Stargate which of itself was supposed to be a transition through time and space,” Trumbull says.

Other innovations followed.

“There was one artist who was in charge of painting the Earth for example, no one had any photographs of the Earth yet, because they had not added orbiting satellites yet,” says Trumbull. “And so, he worked out this technique painting with water colors on glass and then painting the clouds on glass and then going back and scratching it with a razor blade which started creating things that simulated the way clouds naturally form on the Earth. Then, I painted all the stars in the movie. All the stars are spattered white paint from my airbrush onto black shiny paper and I’ve worked out this technique of reducing the pressure of the airbrush until it started to sputter, and it would sputter stars which would become completely irregular and very natural looking, not like I painted them with a paintbrush, which would look artificial.”

Trumbull compares Kubrick’s filming of “2001” to today’s all-immersive Virtual Reality filmmaking:

“You know, the time when the ‘2001’ was made, it was in a time of Cinerama and these 70-millimeter spectacles of “Sound of Music,” “West Side Story,” and giant-screen theaters and you would go out, it was a big deal to go out to see a big-screen movie.”

Today, he says, the equivalent all immersive 360-degree filming and viewing would be virtual reality.

“A lot of people want to have their virtual reality experience, they want to go into another dimension, they want to have some experience that transcends their everyday reality. That’s what I think virtual reality promises.”

Equally significant to the film’s technology is the plot.

“The story it was trying to express was extremely cosmic and very big. Because the idea was that some super intelligent highly evolved civilization way beyond our imagination that to us would look like a god would be incomprehensible to us, like magic, was intervening in human affairs from time to time just to make sure we got through,” says Trumbull.

A powerful sub plot was the antagonistic relationship between man and artificial intelligence. Hal, the ship’s malfunctioning central computer, and Bowman, clash over the ship’s control.

Bowman prevails. His psychedelic-looking passage through the Stargate ends in a static hotel room the aliens have recreated from his memory in order to make contact with him in a different dimension. There, on the bed, Bowman, a very old man, is dying before he gets transformed into a transparent star child.

To celebrate the film’s 50th anniversary, artist Simon Birch recreated that hotel room at the Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C. Exhibit curator Martin Collins explains the lasting power of the film.

“The movie did not seek to pose specific answers to its largest questions. What would be the fruits of space exploration, what would be the potential meaning of contact with extra-terrestrials, what would be the possible transformations that might occur to humanity as it undertakes exploration outside the planet? So, all of these larger questions are kind of implied here in this room and I think we hope that these visitors will sit back a little bit and think about why this room is here and think about this larger set of questions that Kubrick and Clark posed in “2001: (A Space Odyssey).”

The film has been remastered in HD format and has been released in IMAX theaters to celebrate its 50th anniversary. It feels as contemporary as ever.

“I think the movie has stood all these 50 years because it’s unique, it’s spectacularly beautiful, it’s 70mm giant screen. You have to see it on a giant screen to say ‘ah, now I understand why it’s so beautiful, and why these shots last so long, because they are worth looking at. And then the story is this very cosmic evolutionary future looking. And so, when the movie is over, there is a lot to think about,” says Trumbull.

With information from VOA