When migrants go home, they bring back money, skills and ideas that can change a country

Deportees and other migrants return home wealthier, more educated and with more work experience than people who never left. This ‘brain gain’ benefits the whole community, financially and politically.

Escaping violence, war, poverty and environmental disaster, more people than ever are migrating worldwide. Some 258 million people – 3.4% of the global population – live outside their country of birth.

In 1970, about 2% of the world’s 3.7 billion people lived abroad. Historically, those immigrants would have settled where they landed, raised families and joined a new society.

Today, however, more migrants are returning home, whether by choice or by force. Between 1990 to 2015, nearly half of all migrants worldwide went back to their country of birth.

Migrants come home different than when they left, studies show. They are wealthier, multilingual and more educated than most in their local community. Migrants also have more work experience than people who have never lived abroad, as well as bigger social networks and novel technical abilities acquired in foreign schools and jobs.

As a result, their homecomings are a kind of “brain gain” that benefit not just a migrant’s family but also the community – even their country.

Agents of change

After lengthy stays in Western European and North America, for example, migrants from Mali have been shown to bring back democratic political norms that contribute to higher electoral participation. They also demand more integrity from government officials, which encourages political accountability.

Researchers in Cape Verde have documented similar improvements in political accountability and transparency in communities with relatively more return migrants.

Migration doesn’t always engender positive changes. Filipinos returning from stints in the Middle East, for example, are frequently less supportive of democracy when they get home. And the Los Angeles street gang MS-13 took root in Central America after the U.S. deported hundreds of its members to El Salvador in the early 2000s.

Along with economists José Bucheli and Matías Fontenla, I have studied the impact of return migration on Mexico. Today, more Mexicans are leaving the U.S. than going to it.

Our research builds on a 2011 study that Mexican households with at one least return migrant reported higher access to disposable income and funds for investment, as well as better access to clean water, dependable electricity, better-quality housing and education.

With data analysis and in-person interviews in Guanajuato state, we determined that migrants returning to Mexico actually improve living conditions for many others in their communities, too. Return migrants tap into the new skills they’ve acquired abroad – like fluent English – to promote local economic development, creating jobs, increasing wealth and demanding more government accountability.

Many call centers in Latin America, like the Firstkontact Center in Tijuana, employ U.S. deportees who can provide English-language customer service for American companies, Aug. 13, 2014.

Many call centers in Latin America, like the Firstkontact Center in Tijuana, employ U.S. deportees who can provide English-language customer service for American companies, Aug. 13, 2014.AP Photo/Alex Cossio

One return migrant I met in 2011 said he tried to run his tortilla stand “like my bosses ran their businesses back in the U.S.”

“I open every day at the same time, I pay attention to quality control and I always make the customer my priority,” he said.

Several other Mexicans who’d lived in the U.S. told me they now expected more of public officials. They expressed disgust, for example, at the corruption of the Mexican police, who can be bribed out of ticketing drivers.

“I’ve seen how things can work differently and I’m now determined to contribute to a better Mexico,” one man told me.

The presence of return migrants actually reduces the likelihood of violence in Mexico, our research shows. There, when migrants come home, they inject their hometowns with much-needed social and human capital. That creates a kind of local revival that leads crime to drop.

Juan Aguilar: The entrepreneurial deportee

The next phase of my research on return migration is focused on Nicaragua.

Between the Somoza dictatorship of the 1970s, the revolution that ousted his regime, the civil war of the 1980s and, most recently, the political strife of Daniel Ortega’s presidency, waves of people from all social classes have fled Nicaragua in recent decades.

I have interviewed more than 70 Nicaraguans who’ve since returned home. Their personal stories are varied, but they share a common denominator: Drawing on their experiences abroad, they are changing Nicaragua.

“I grew up in LA. And now I live here, in a country I never knew,” Juan Aguilar, an imposing man with a fading teardrop tattoo near his left eye and the letters “L.A.” inked under his baseball cap, told me in unaccented English.

Aguilar was carried into the U.S. on foot by his mom at the age of 2. In 2010, he was deported for dealing drugs and gang activity.

“I was devastated at first. I wanted to go back,” he said over cappuccino at Managua’s Casa del Café in March 2018. “But I’m happy here now. I wouldn’t go back even if I had the chance.”

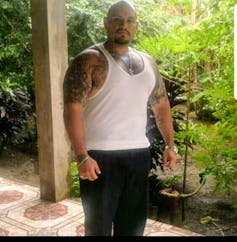

Juan Aguilar in Managua, shortly after being deported.

Juan Aguilar in Managua, shortly after being deported.Juan Aguilar, Author provided

Juan and his partner, Sarah, own five call centers in Managua that provide customer service for U.S. health care providers, student loan companies and other lucrative businesses.

The call centers employ more than 100 people, more than half of whom are U.S. deportees who speak English, the most widely spoken language in the world.

“We try to give people the benefit of the doubt,” he said of their brushes with the law.

Even doctors work at Juan and Sarah’s call centers. There, they can make up to US$1,000 a month – twice what they’d make in Nicaragua’s crumbling public hospitals.

I asked Juan what explained his seemingly unlikely success story as an entrepreneur.

“English,” he said. “And the fact that I know how to run a business. Those are things I learned in the States.”

Piero Bergman, the CEO

Piero Bergman and his family left civil war in Nicaragua during the 1980s for Boca Raton, Florida. As upper-class Nicaraguans, they arrived to the United States with visas in hand.

When Bergman returned to Nicaragua in the late 1990s after decades in the telecommunications industry, he came back with a business idea: cyber cafes.

“I was traveling a lot, 60-something countries a year,” he told me. “I used to go to internet cafes frequently, particularly in Argentina.”

In Buenos Aires, internet cafes dotted the streets. Managua, Bergman’s hometown, had none.

Bergman launched a chain of cybercafes in Managua, bringing publicly accessible internet to the Central American country.

“The thing took off, and we put them up nationwide,” he said. Eventually, Bergman’s company was providing IP services to over 1,500 internet cafes across the country.

After in-home internet undercut Piero’s businesses, he shifted his focus to digital security. Today, Piero is the president of Intelligent Solutions, a Nicaraguan electronic security company with more than 100 employees.

Bergman attributes his success to the time he spent living and traveling abroad.

“I came down here with a different mindset and ideas about how to do things,” he said.

Benjamin Waddell, Associate Professor of Sociology, Fort Lewis College

Este artículo fue publicado originalmente en The Conversation. Lea el original. Foto: Shutterstock