Why Religions of the World Condemn Suicide

Mathew Schmalz, College of the Holy Cross

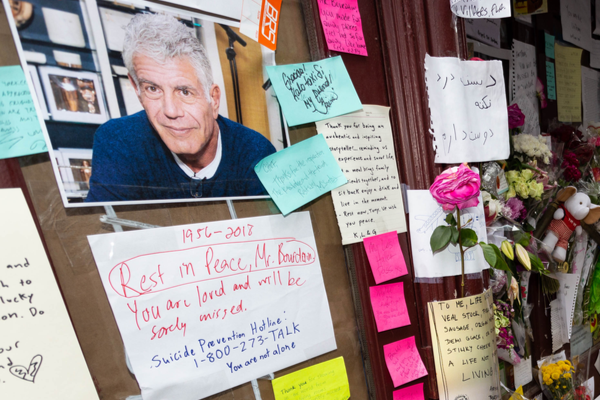

The recent suicides of fashion designer Kate Spade and celebrity chef and writer Anthony Bourdain have reminded all of us that, even for the wealthy, life can become too painful to bear.

The sad truth is that suicide rates have been increasing in the United States. In the last decade, the suicide rate increased by nearly 30 percent, with women and teens particularly affected.

And it’s not just the United States. Suicide is increasingly taking a toll on individuals and families throughout the world.

The ethics of self-inflicted death have historically been an important area of reflection for the world’s religions.

Whose life is it?

Many of the world’s religions have traditionally condemned suicide because, as they believe, human life fundamentally belongs to God.

Jossifresco, revisions by AnonMoos

In the Jewish tradition, the prohibition against suicide originated in Genesis 9:5, which says, “And for your lifeblood I will require a reckoning.” This means that humans are accountable to God for the choices they make. From this perspective, life belongs to God and is not yours to take. Jewish civil and religious law, the Talmud, withheld from a suicide the rituals and treatment that were given to the body in the case of other deaths, such as burial in a Jewish cemetery, though this is not the case today.

A similar perspective shaped Catholic teachings about suicide. St. Augustine of Hippo, an early Christian bishop and philosopher, wrote that “he who kills himself is a homicide.” In fact, according the Catechism of St. Pius X, an early 20th-century compendium of Catholic beliefs, someone who died by suicide should be denied Christian burial – a prohibition that is no longer observed.

The Italian poet Dante Aligheri, in “The Inferno,” extrapolated from traditional Catholic beliefs and placed those who had committed the sin of suicide on the seventh level of hell, where they exist in the form of trees that painfully bleed when cut or pruned.

According to traditional Islamic understandings, the fate of those who die by suicide is similarly dreadful. Hadiths, or sayings, attributed to the Prophet Muhammad warn Muslims against committing suicide. The hadiths say that those who kill themselves suffer hellfire. And in hell, they will continue to inflict pain on themselves, according to the method of their suicide.

In Hinduism, suicide is referred to by the Sanskrit word “atmahatya,” literally meaning “soul-murder.” “Soul-murder” is said to produce a string of karmic reactions that prevent the soul from obtaining liberation. In fact, Indian folklore has numerous stories about those who commit suicide. According to the Hindu philosophy of birth and rebirth, in not being reincarnated, souls linger on the earth, and at times, trouble the living.

Buddhism also prohibits suicide, or aiding and abetting the act, because such self-harm causes more suffering rather than alleviating it. And most basically, suicide violates a fundamental Buddhist moral precept: to abstain from taking life.

Altruistic suicide

While many religions have traditionally prohibited suicide when motivated by despair, certain forms of suicide, for the community or for a greater good, are permitted, and at times, even celebrated.

In his classic work “On Suicide,” French sociologist Emile Durkheim used the term “altruistic suicide” to describe the act of killing oneself in the service of a higher principle or the greater community. And consciously sacrificing one’s life for God, or for other religious ends, has historically been the most prominent form of “altruistic suicide.”

Recently, Pope Francis has added another category for sainthood, that of giving up one’s life for another, called “oblatio vitae.” Of course, both Christianity and Islam have strong conceptions of martyrdom, which also extend to intentionally giving one’s life in battle. For example, the Crusader Hugh the Insane self-destructively leapt out of the tower of a besieged castle in order to crush and kill Turkish soldiers below.

AP Photo/Ashwini Bhatia

Buddhist monks have burned themselves to death, most famously in Vietnam, but also in Tibet, to draw attention to violence and oppression. And within Hinduism, there is a tradition of ascetics fasting to death after they gained enlightenment. Then there are the ancient Hindu traditions of “sati”, where the wife dies on her husband’s funeral pyre, and “jauhar”, the ritual self-immolation of an entire community of women when they were certain of defeat in war and consequent enslavement.

What unifies all these examples is the idea that there are principles or goals that are more important than life itself. And so, self-sacrifice is not suicide: letting go of life because of faith is different, from letting go of life because of lack of hope.

Rethinking suicide

While striving to emphasizing the sacredness of life, it’s most certainly the case that traditional religious prohibitions against suicide provide little comfort to those who contemplate taking their own life, not to mention to the loved ones who will be left behind.

The good news is that today, there are more and more resources for talking about and preventing suicide. In particular, world religions have become more sympathetic and nuanced in their understanding. Jews, Catholics, Muslims, Buddhists and Hindus have all established extensive outreach programs to those who suffer from suicidal thoughts.

Such efforts recognize that God especially loves those who suffer in the darkness of depression. Suicide then is not an act that calls for divine punishment, but an all-too-common threat that calls us to reaffirm hope in life as a precious gift given by God.

Mathew Schmalz, Associate Professor of Religion, College of the Holy Cross

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.