What is heaven?

Joanne M. Pierce, College of the Holy Cross

When a family member or a friend passes away, we often find ourselves reflecting on the question “where are they now?” As mortal beings, it is a question of ultimate significance to each of us.

Different cultural groups, and different individuals within them, respond with numerous, often conflicting, answers to questions about life after death. For many, these questions are rooted in the idea of reward for the good (a heaven) and punishment for the wicked (a hell), where earthly injustices are finally righted.

However, these common roots do not guarantee contemporary agreement on the nature, or even the existence, of hell and heaven. Pope Francis himself has raised Catholic eyebrows over some of his comments on heaven, recently telling a young boy that his deceased father, an atheist, was with God in heaven because, by his careful parenting, “he had a good heart.”

So, what is the Christian idea of “heaven”?

Beliefs about what happens at death

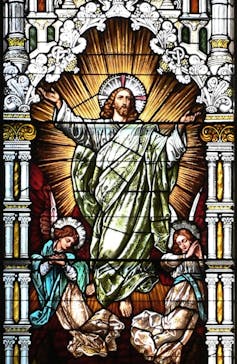

The earliest Christians believed that Jesus Christ, risen from the dead after his crucifixion, would soon return, to complete what he had begun by his preaching: the establishment of the Kingdom of God. This Second Coming of Christ would bring an end to the effort of unification of all humanity in Christ and result in a final resurrection of the dead and moral judgment of all human beings.

Waiting For The Word, CC BY

By the middle of the first century A.D., Christians became concerned about the fate of members of their churches who had already died before this Second Coming.

Some of the earliest documents in the Christian New Testament, epistles or letters written by the apostle Paul, offered an answer. The dead have simply fallen asleep, they explained. When Christ returns, the dead, too, would rise in renewed bodies, and be judged by Christ himself. Afterwards, they would be united with him forever.

A few theologians in the early centuries of Christianity agreed. But a growing consensus developed that the souls of the dead were held in a kind of waiting state until the end of the world, when they would be once again reunited with their bodies, resurrected in a more perfected form.

Promise of eternal life

After Roman Emperor Constantine legalized Christianity in the early fourth century, the number of Christians grew enormously. Millions converted across the Empire, and by the century’s end, the old Roman state religion was prohibited.

Based on the Gospels, bishops and theologians emphasized that the promise of eternal life in heaven was open only to the baptized – that is, those who had undergone the ritual immersion in water which cleansed the soul from sin and marked one’s entrance into the church. All others were damned to eternal separation from God and punishment for sin.

In this new Christian empire, baptism was increasingly administered to infants. Some theologians challenged this practice, since infants could not yet commit sins. But in the Christian west, the belief in “original sin” – the sin of Adam and Eve when they disobeyed God’s command in the Garden of Eden (the “Fall”) – predominated.

Following the teachings of the fourth century saint Augustine, Western theologians in the fifth century A.D. believed that even infants were born with the sin of Adam and Eve marring their spirit and will.

But this doctrine raised a troubling question: What of those infants who died before baptism could be administered?

At first, theologians taught that their souls went to Hell, but suffered very little if at all.

The concept of Limbo developed from this idea. Popes and theologians in the 13th century taught that the souls of unbaptized babies or young children enjoyed a state of natural happiness on the “edge” of Hell, but, like those punished more severely in Hell itself, were denied the bliss of the presence of God.

Giovanni di Paolo

Time of judgment

During times of war or plague in antiquity and the Middle Ages, Western Christians often interpreted the social chaos as a sign of the end of the world. However, as the centuries passed, the Second Coming of Christ generally became a more remote event for most Christians, still awaited but relegated to an indeterminate future. Instead, Christian theology focused more on the moment of individual death.

Judgment, the evaluation of the moral state of each human being, was no longer postponed until the end of the world. Each soul was first judged individually by Christ immediately after death (the “Particular” Judgment), as well as at the Second Coming (the Final or General Judgment).

Deathbed rituals or “Last Rites” developed from earlier rites for the sick and penitent, and most had the opportunity to confess their sins to a priest, be anointed, and receive a “final” communion before breathing their last.

Medieval Christians prayed to be protected from a sudden or unexpected death, because they feared baptism alone was not enough to enter heaven directly without these Last Rites.

Another doctrine had developed. Some died still guilty of lesser or venial sins, like common gossip, petty theft, or minor lies that did not completely deplete one’s soul of God’s grace. After death, these souls would first be “purged” of any remaining sin or guilt in a spiritual state called Purgatory. After this spiritual cleansing, usually visualized as fire, they would be pure enough to enter heaven.

Only those who were extraordinarily virtuous, such as the saints, or those who had received the Last Rites, could enter directly into heaven and the presence of God.

Images of heaven

In antiquity, the first centuries of the Common Era, Christian heaven shared certain characteristics with both Judaism and Hellenistic religious thought on the afterlife of the virtuous. One was that of an almost physical rest and refreshment as after a desert journey, often accompanied by descriptions of banquets, fountains or rivers. In the Bible’s Book of Revelation, a symbolic description of the end of the world, the river running through God’s New Jerusalem was called the river “of the water of life.” However, in the Gospel of Luke, the damned were tormented by thirst.

Another was the image of light. Romans and Jews thought of the abode of the wicked as a place of darkness and shadows, but the divine dwelling place was filled with bright light. Heaven was also charged with positive emotions: peace, joy, love, and the bliss of spiritual fulfillment that Christians came to refer to as the Beatific Vision, the presence of God.

Fra Angelico

Visionaries and poets used a variety of additional images: flowering meadows, colors beyond description, trees filled with fruit, company and conversation with family or white-robed others among the blessed. Bright angels stood behind the dazzling throne of God and sang praise in exquisite melodies.

The Protestant Reformation, begun in 1517, would break sharply with the Roman Catholic Church in Western Europe in the 16th century. While both sides would argue about the existence of Purgatory, or whether only some were predestined by God to enter heaven, the existence and general nature of heaven itself was not an issue.

Heaven as the place of God

Today, theologians offer a variety of opinions about the nature of heaven. The Anglican C. S. Lewis wrote that even one’s pets might be admitted, united in love with their owners as the owners are united in Christ through baptism.

Following the nineteenth-century Pope Pius IX, Jesuit Karl Rahner taught that even non-Christians and non-believers could still be saved through Christ if they lived according to similar values, an idea now found in the Catholic Catechism.

The Catholic Church itself has dropped the idea of Limbo, leaving the fate of unbaptized infants to “the mercy of God.” One theme remains constant, however: Heaven is the presence of God, in the company of others who have responded to God’s call in their own lives.

Joanne M. Pierce, Professor of Religious Studies, College of the Holy Cross

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.