W.E.B. Du Bois, Black History Month and the importance of African American studies

As the 20th century’s preeminent scholar-activist on race, W.E.B. Du Bois would not be surprised by modern-day attempts at whitewashing American history. He saw them in 1930s and 1940s.

The opening days of Black History Month 2023 have coincided with controversy about the teaching and broader meaning of African American studies.

On Feb. 1, 2023, the College Board released a revised curriculum for its newly developed Advanced Placement African American studies course.

Critics have accused the College Board of caving to political pressure stemming from conservative backlash and the decision of Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis to ban the course from public high schools in Florida because of what he characterized as its radical content and inclusion of topics such as critical race theory, reparations and the Black Lives Matter movement.

On Feb. 11, 1951, an article by the 82-year-old Black scholar-activist W.E.B. Du Bois titled “Negro History Week” appeared in the short-lived New York newspaper The Daily Compass.

As one of the founders of the NAACP in 1909 and the editor of its powerful magazine The Crisis, Du Bois is considered by historians and intellectuals from many academic disciplines as America’s preeminent thinker on race. His thoughts and opinions still carry weight throughout the world.

Du Bois’ words in that 1951 article are especially prescient today, offering a reminder about the importance of Black History Month and what is at stake in current conversations about African American studies.

Du Bois began his Daily Compass commentary by praising Carter G. Woodson, founder of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, who established Negro History Week in 1926. The week would eventually become Black History Month.

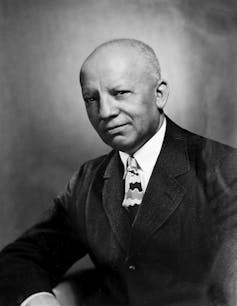

Black historian Carter G. Woodson in 1946.

Black historian Carter G. Woodson in 1946.Library of Congress

Du Bois described the annual commemoration as Woodson’s “crowning achievement.”

Woodson was the second African American to earn a doctorate in history from Harvard University. Du Bois was the first.

Du Bois and Woodson did not always see eye to eye. However, as I explore in my new book, “The Wounded World: W.E.B. Du Bois and the First World War,” the two pioneering scholars always respected each other.

Reckoning with history and reclaiming the past

Du Bois’ connection to and appreciation of Negro History Week grew during the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s. During this time, whether in public speeches or published articles, he never missed an opportunity to acknowledge the importance of Negro History Week.

In the Feb. 11, 1951, article, Du Bois reflected that his own contributions to Negro History Week “lay in my long effort as a historian and sociologist to make America and Negroes themselves aware of the significant facts of Negro history.”

Summarizing his work from his first book, “The Suppression of the African Slave-Trade,” published in 1896, through his magnum opus “Black Reconstruction in America,” published in 1935, Du Bois told readers of the Daily Compass piece that much of his career was spent trying “to correct the distortion of history in regard to Negro enfranchisement.”

By doing so, the nation would hopefully become, Du Bois wrote further, “conscious that this part of our citizenry were normal human beings who had served the nation credibly and were still being deprived of their credit by ignorant and prejudiced historians.”

In addition to championing Negro History Week, Du Bois applauded other Black scholars, like E. Franklin Frazier, Charles Johnson and Shirley Graham, who were “steadily attacking” the omissions and distortions of Black people in school textbooks.

Du Bois went on to chronicle the achievements of African Americans in science, religion, art, literature and the military, making clear that Black people had a history to be proud of.

W.E.B. Du Bois, third from right in the second row, joins other marchers in New York protesting against racism on July 28, 1917.

W.E.B. Du Bois, third from right in the second row, joins other marchers in New York protesting against racism on July 28, 1917.George Rinhart/Corbis via Getty Images

Du Bois, however, questioned what deeper meaning these achievements held to the issues facing Black people in the present.

“What now does Negro History Week stand for?” he asked in the 1951 article. “Shall American Negroes continue to learn to be ‘proud’ of themselves, or is there a higher broader aim for their research and study?”

“In other words,” he asserted, “as it becomes more universally known what Negroes contributed to America in the past, more must logically be said and taught concerning the future.”

The time had come, Du Bois believed, for African Americans to stop striving to be merely “the equal of white Americans.”

Black people needed to cease emulating the worst traits of America – flamboyance, individualism, greed and financial success at any cost – and support labor unions, Pan-Africanism and anti-colonial struggle.

He especially encouraged the systematic study of the imperial and economic roots of racism: “Here is a field for Negro History Week.”

Black history and Black struggle

Looking ahead, Du Bois declared that if Negro History Week remained “true to the ideals of Carter Woodson” and followed “the logical development of the Negro Race in America,” it would not confine itself to the study of the past nor “boasting and vainglory over what we have accomplished.”

“It will not mistake wealth as the measure of America, nor big-business and noise as World Domination,” Du Bois wrote in his article.

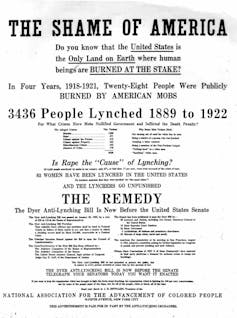

In 1922, the NAACP ran a series of full-page ads in The New York Times calling attention to lynchings.

In 1922, the NAACP ran a series of full-page ads in The New York Times calling attention to lynchings.New York Times, Nov. 23, 1922/American Social History Project

Instead, Du Bois believed Negro History Week would “concentrate on study of the present,” “not be afraid of radical literature” and, above all else, advocate for peace and voice “eternal opposition against war between the white and colored peoples of the earth.”

Were he alive today, Du Bois would certainly have much to say about current debates around the teaching of African American history and the larger significance of African American studies. Du Bois died on Aug. 27, 1963, in Accra, Ghana.

But he left behind his clairvoyant words that remind us of the connections between African American studies and movements for Black liberation, along with how the teaching of African American history has always challenged racist and exclusionary narratives of the nation’s past.

Du Bois also reminds us that Black History Month is rooted in a legacy of activism and resistance, one that continues in the present.

Chad Williams, Samuel J. and Augusta Spector Professor of History and African and African American Studies, Brandeis University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.