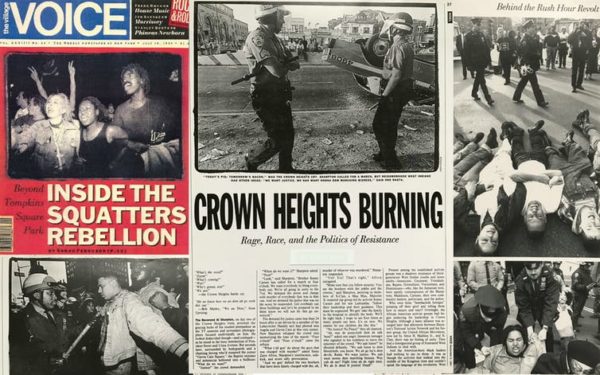

The Village Voice’s photographers captured change, turmoil unfolding on New York City’s streets

When The Village Voice, the nation’s first alternative weekly, closed in late August, social justice movements lost one of their biggest cheerleaders.

Founded in 1955, the Voice aggressively covered civil rights, race relations, police brutality, gentrification, homelessness and reproductive rights. While a gay rights march may have received a short mention in The New York Times, that same demonstration would get front page treatment in the Voice.

The Voice played a particularly important role in promoting and publishing social documentary photography.

Just as the photographs of Lewis Hine and Jacob Riis communicated the horrors of child labor and tenement overcrowding in the early 20th century, Voice photojournalists such as Donna Binder, Ricky Flores, Lisa Kahane, T.L. Litt, Thomas McGovern, Brian Palmer, Joseph Rodriguez, and Linda Rosier conveyed the fears, rage and struggles of the city’s marginalized communities.

In issue after issue, these photographers captured the despair and anger of the HIV/AIDS epidemic; the anguish of black and Latino New Yorkers whose friends and family members had died at the hands of white mobs or the police; and battles over access to affordable housing.

Their work is included in “Whose Streets? Our Streets!,” a traveling exhibition that we co-curated with Meg Handler and Michael Kamber and that features photojournalists who covered struggles for social justice on the streets of New York City from 1980 to 2000.

We spoke with Handler, a former photo editor for the Voice, and three photographers whose work regularly appeared in the publication to discuss the significance of the Voice’s approach to photography.

An unabashedly activist approach

Founded in 1955, The Village Voice quickly became a popular outlet for progressive photojournalists.

To Handler, a former photo editor of the Voice in the early 1990s, there were three key points of attraction:

“One, there was never any ambiguity about the politics of the paper. It was, from its infancy, what longtime Voice photo editor and photographer Fred W. McDarrah famously called a ‘commie, hippie, pinko rag.’ Two, the paper hired a fair amount of freelancers and so there was the opportunity to work with a diverse group of people to cover subjects that they were personally committed to. And three, it was a ‘photographer’s paper,’ meaning images would retain their integrity, they wouldn’t be cropped, their subjects wouldn’t be misrepresented.”

Photographer Tom McGovern worked at the Voice from 1988 to 1995, and credited the publication with giving him the freedom to make the photographs he wanted to make in order to educate others about the AIDS epidemic.

McGovern, whose photographs of the AIDS crisis would eventually be published in his 1999 book, “Bearing Witness (To AIDS),” told us that he was motivated by a simple impulse: to “challenge the negative stereotypes about who has AIDS and what is this disease.”

“It was not traditional journalism,” he said. “I never saw myself as being completely objective. I was certainly a supporter of the cause.”

In his photographs, McGovern highlighted the work of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or ACT UP New York, which used direct action and spectacular street theater to call attention to the ineffective government response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

CC BY-SA199 KB (download)

“[ACT UP] knew how to stage events,” McGovern said. He explained that the organization’s members would plan demonstrations for late afternoon, when the lighting is best for snapping photographs. They also created these “beautiful posters that were made to be photographed great.”

In this way, AIDS activists collaborated with photojournalists to promote support for AIDS research and to challenge the stigma of the disease.

The eyes of the neighborhood

Social documentary photographers are committed to showcasing perspectives of marginalized groups. Dorothea Lange famously told the story of the Great Depression through the faces of destitute farming families, not wealthy bankers.

Sometimes, those best suited to tell the stories of marginalized groups came from those groups themselves.

The Village Voice, more than mainstream news outlets, valued publishing work by photographers from diverse backgrounds.

Ricky Flores, whose photographs document race relations and police brutality, was raised in the South Bronx. According to Flores, his own background and community ties were essential to the pictures he made for the Voice and other progressive outlets.

Other photographers aren’t “going to see it the way I see it,” Flores said. “They’re not a South Bronx Puerto Rican who actually is living under the very weight of the oppression that was being focused on our community.”

In addition to photographing the South Bronx and Puerto Rican activism, Flores is known for his coverage of race relations and police brutality.

He photographed the civil rights marches led by Rev. Al Sharpton in the late 1980s and early 1990s after white youth killed a young African-American man in Howard Beach. He also covered the unrest in Washington Heights in July 1992 following the police killing of Jose “Kiko” Garcia in a drug sweep.

CC BY-SA181 KB (download)

In an interview, Flores said that through his work, he hoped to show “why people are demonstrating,” by documenting “the injustices that were taking place.”

To this day, “there’s a lot of mistrust” of the police in minority communities, Flores continued. “They feel that cops can get away with murdering citizens with impunity.”

A ‘mandate’ to capture and make sense of it all

With its focus on local issues and its tradition of muckraking journalism, the Voice gave social justice movements more coverage – and more sympathetic coverage – than mainstream papers like The New York Times.

As a student activist at New York University in the 1980s, Victoria Wolcott recalled how, after a protest, “you would go and get the Village Voice the next day. We wanted to know what the Village Voice was reporting, because they were progressive and they had really great photographs.”

The Voice’s coverage of the 1988 Tompkins Square Park riots – in which police charged a crowd of homeless people, activists and journalists protesting the city’s implementation of a curfew in the park – helped participants make sense of what they were seeing unfolding on the streets.

Wolcott, now a professor of history at the University of Buffalo, explained how “there would be a photograph of somebody getting beat up [by the police] with blood [gushing] from their head, so that was another way that photographs help to legitimize … your experience.”

Voice photographer Linda Rosier told us that in those years, before the rise of smart phones, social media and so-called citizen journalism, she had a “mandate” to photograph, “since we were the ones out there seeing it and being the eyes of the city really.”

CC BY198 KB (download)

Today, McGovern adds, “Newspapers and magazines don’t have the power they used to have. It’s not like you’re waiting for The Village Voice to come out on Wednesday or The New York Times the next morning to be able to see these pictures; now it’s on social media.”

The problem now is not a dearth of images, but rather a lack of context.

Part of a photograph’s power can come from the way experienced journalists and editors position it in the text, or use it to complement a reported article. Social documentary photographers also spent years immersing themselves in the community they were covering and cultivating ties to activists. They possessed a deep knowledge of their subject.

The tactics and spirit of the Voice might live on in the amateur photographers covering modern social movements like Black Lives Matter and the Keystone XL Pipeline.

But something will be lost with the folding of a periodical that featured images by the neighborhood, about the neighborhood and for the neighborhood.

Tamar Carroll, Associate Professor of History, Rochester Institute of Technology and Joshua Meltzer, Assistant Professor of Photojournalism and Visual Storytelling, Rochester Institute of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.