The Amish live simply, but don’t confuse them with environmentalists

In recent decades, many popular myths about the Amish – that they are dying out, or are a homogeneous community of technophobes, or are “stuck in the past” – have been convincingly dispelled. Yet the perception that they seek to live in harmony with nature is alive and well.

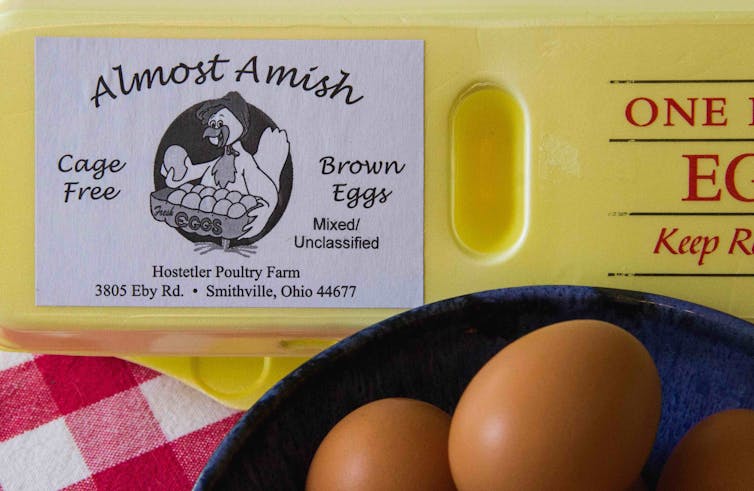

Today’s Amish brand, whether attached to furniture, quilts or fresh produce, has become synonymous with a rural, wholesome and authentic lifestyle. And because many outsiders view the Amish as closely tied to the land, distancing themselves from modern conveniences, they naturally assume that the Amish embrace an environmentally minded lifestyle.

Doyle Yoder, CC BY-ND

We were curious about how this prevailing notion of the back-to-nature, environmentally conscious Amish fit with their biblical understandings and with the changing realities of their lives. Drawing on our respective training in cultural anthropology and ecology, we spent the last seven years exploring Amish engagements with nature from multiple angles.

In our new book, “Nature and the Environment in Amish Life,” we argue that while there is considerable diversity across Amish groups and regions, they generally regard nature as being specifically created by God for human use. Their responses to regional and global environmental issues, such as watershed pollution and climate change, also reveal a deep skepticism of environmentalism and the regulatory state.

Our approach

The Amish are one of the fastest growing ethno-religious groups in North America. Their population, which currently numbers 330,000 in 31 states and four Canadian provinces, doubles about every 20 years.

To get a comprehensive view, we conducted ethnographic research in 12 states and 35 Amish settlements, interviewing over 150 Amish and 30 former or non-Amish individuals. We also conducted a survey of household resource use among rural Amish and non-Amish residents in Ohio.

We examined how the Amish thought about and engaged with nature at home and school, at work, at leisure, and in their responses to local and global environmental concerns.

Marilyn Loveless, CC BY-ND

Growing up rural

A rural Amish childhood provides many opportunities for children to interact with nature in daily chores and outdoor play. This contrasts starkly with the technologically mediated childhood prevalent in wider U.S. society.

Yet we found that Amish “closeness to nature” takes place within a very specific cultural idiom that sees nature as a manifestation of God’s handiwork, created for the benefit of humans. “It wouldn’t be a popular thing to say in society,” one New Order Amish man told us, “but Man is dominant on the earth.”

In eight years of parochial schooling, Amish children may undertake nature study and go on field trips, but science is rarely a part of the curriculum. They enter adolescence with an intimate knowledge of certain aspects of the landscape in which they live, but minimal scientific understanding of natural processes.

Working with nature

Meanwhile, national economic trends have created significant new challenges and opportunities for using nature to earn a livelihood. Unable to compete with the technology and scale of industrial agriculture, most Amish heads of household have left farming altogether.

Perhaps surprisingly, those who remain generally use pesticides and chemical fertilizers. One exception is a small but growing number of Amish organic cooperatives such as Greenfield Farms, which have made savvy use of the lucrative niche market for organic produce and other products, and benefit from outsider perceptions of the Amish as being wholesome and close to nature.

Doyle Yoder, CC BY-ND

Many Amish work in the wood products industry, where they have carved out a reputation for furniture craftsmanship. With a few exceptions, however, the Amish are not at the forefront of careful logging practices and take a relatively short-term view of forests because they see this world as transient. One Amish sawmill operator told us, “Even though we want to take care of it, it’s not going to be quite as much of a priority if we know it’s temporary.”

Animal breeding has also experienced rapid growth among the Amish. It echoes the farming ethos, using animals for livelihoods, but requires only a few acres of land and can be very lucrative. Dog breeders produce purebred or designer hybrid puppies, while deer breeders select for antler size to create “shooter bucks” that are sold to private hunting preserves.

Dog and deer breeding are controversial even within the Amish community, but both are driven by economic pragmatism and by a willingness to use tools of science, such as artificial insemination, to produce traits desired by and tailored to non-Amish consumers.

Amish responses to environmental issues

We also wondered how the Amish respond to local and global environmental challenges and how they think about ecological limits to human activities.

In several Midwestern states, the Amish have come under fire for farming practices that contribute to watershed degradation, such as spreading manure, or barnyards perched on the banks of creeks.

David McConnell, CC BY-ND

Efforts to remediate the situation are often hampered by deep distrust among the Amish of government, environmentalists and the science that underpins much environmental regulation. “When I think of a scientist, I usually think of an ungodly life,” one businessman told us frankly.

The Amish we spoke with also cast environmentalists as extremists, frequently referring to them as tree huggers or animal rights activists. In one survey we administered, their views were less environmentally inclined than all but one of 69 populations reported by other researchers.

This skepticism does not automatically preclude Amish involvement in solving environmental problems, however. One Amish bishop in Big Valley, Pennsylvania offered a different approach: “Come in and teach us. You can catch a lot more flies with honey.”

When it comes to global issues, the Amish are climate change skeptics. Their large families, which they see as fulfilling God’s mandate, are arguably at odds with the very notion of sustainability. The Amish we interviewed also said they support efforts to protect biodiversity only up to a point. Noting that humans have souls and animals don’t, one Amish man reflected, “We privilege humans. Otherwise, we should just open the doors and let in all the flies.”

Many of these anthropocentric attitudes and approaches are similar to those of their non-Amish rural counterparts, though some Christian evangelicals have embraced the idea of limits to Earth’s resources.

Parochial stewards

Not all Amish practices were inconsistent with their image as ecological stewards. Compared to rural non-Amish, they had a relatively low carbon footprint in transportation and consumption (though not in household energy use), and grew or raised more of their food.

Amish interactions with nature raise the question of the relative importance of intention and outcome as components of an ecological worldview. “I can’t ever remember being taught by my parents about the ecological value of nature,” one young man reflected. Most Amish practices that look ecological are better understood as a by-product of their religious and cultural worldview.

Ultimately, Amish engagements with nature cannot be reduced to a simplistic trope. Rather, they reflect a complicated mix of historical experience, economic pragmatism and cultural and religious understandings. The sooner we can move beyond an idealistic image of the all-natural Amish, the easier it will be to find common ground between Amish and non-Amish communities.

David McConnell, Professor of Anthropology, The College of Wooster and Marilyn Loveless, Professor Emeritus of Biology, The College of Wooster

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. Photo: Shutterstock