Pancakes won’t turn you into a zombie as in HBO’s ‘The Last of Us,’ but fungi in flour have been making people sick for a long time

Raw flour at the store still contains live microorganisms. And while cooking can kill the fungi, it doesn’t destroy any illness-causing mycotoxins that might be present.

In the HBO series “The Last of Us,” named after the popular video game of the same name, the flour supplies of the world are contaminated with a fungus called Cordyceps. When people eat pancakes or other foods made with that flour, the fungi grow inside their bodies and turn them into zombies.

As a food scientist, I study the effect of processing on the quality and safety of fruits and vegetables, including the flour used to make pancakes. While no one is going to turn into a zombie from eating pancakes in real life, flour is often contaminated with fungi that can produce mycotoxins that make people sick. Proper processing and cooking, however, can generally keep you safe.

How common is fungi in flour?

People have been eating bread made from wheat for approximately 14,000 years and cultivating wheat for at least 10,000 years. In 1882, “drunken bread disease” was first documented in Russia, where people reported dizziness, headache, trembling hands, confusion and vomiting after eating bread. Long before that, Chinese peasants were reporting that eating pinkish wheat – a key sign of infection with a mold called Fusarium – caused them to feel ill. Clearly, fungi have been making people sick for a long time.

Wheat, corn, rice and even fruits and vegetables can be infected with fungi as they grow in the field. In “The Last of Us,” an epidemiologist theorizes that climate change is causing the fungus to mutate so it can infect humans. The unfortunate reality is that fungi have become more of a problem in recent years as warmer temperatures encourage their growth.

A 2017 study found that over 90% of wheat and corn flour samples in Washington, D.C., contained live fungi, with Aspergillus and Fusarium the predominant types of mold in wheat flour. Fusarium grows on wheat in the field and can cause a common agricultural plant disease called fusarium head blight, or scab.

Farmers use multiple techniques to reduce this devastating plant disease, including implementing crop rotation, using resistant varieties and fungicides and minimizing irrigation during flowering. After harvesting, they sort the grains to remove contaminated wheat before grinding them into flour. While sorting removes most of the contaminated wheat, small amounts of fungi can still make it into the flour.

Wheat infected with fusarium head blight have a characteristic pink hue.

Wheat infected with fusarium head blight have a characteristic pink hue.Tomasz Klejdysz/iStock via Getty Images Plus

Killing microorganisms in flour

The good news is that most fungi and other microorganisms die at 160-170 degrees Fahrenheit (71-77 degrees Celsius). Pancakes are typically cooked to an internal temperature of 190-200 F (88-93 C). Other cakes and breads are cooked to internal temperatures anywhere from 180 to 210 degrees Fahrenheit (82-99 C). So, unlike in “The Last of Us,” as long as you bake or fry your dough, you’ll have killed the fungi.

The problem comes when people eat the flour without cooking it first, such as by consuming raw cookie dough or “licking the bowl clean.” Both raw egg and raw flour can contain microorganisms that make people sick. The microorganisms that public health officials are most worried about are E. coli and Salmonella, dangerous pathogens that can cause severe illness.

Most people don’t realize that the flour they buy at the store is raw flour that still contains live microorganisms. Flour is rarely commercially treated to be safe to eat raw because consumers almost always cook flour-based foods. While consumers can also attempt to heat-treat raw flour at home, this isn’t recommended because the flour may not be spread thinly enough to kill all of the microorganisms.

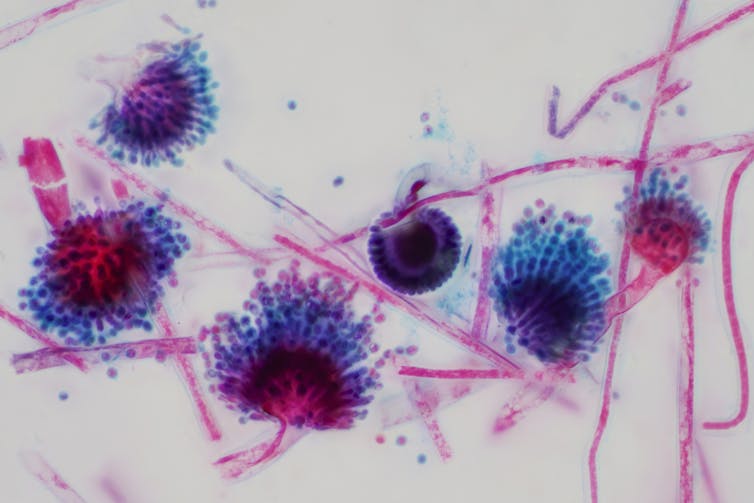

Aspergillus is one of the predominant molds found in wheat flour.

Aspergillus is one of the predominant molds found in wheat flour.tonaquatic/iStock via Getty Images Plus

Some fungi and microorganisms can create spores, which are like seeds that help them survive adverse conditions. These spores can survive cooking, drying and freezing. There are even 4,500-year-old yeast spores that have been reawakened and made into bread. These fungal spores rarely cause serious illness in people, except in those with weakened immune systems.

Chemicals can be added to food to stop fungal growth. These additives include sorbates, benzoates and propionates. However, you almost never see these additives in flour or pancake mix because fungi can’t grow in a dry powder. The fungi either grew on the wheat in the field or on the bread after it is baked. For that reason, you may see these additives in bread but not in a powdered mix.

Mycotoxins

The biggest risk from fungi is not that it will grow inside our bodies, but that it will grow on wheat or other foods and produce chemicals called mycotoxins that can cause severe health problems. When wheat is harvested and ground into flour, mycotoxins can get mixed in.

Unfortunately, while normal cooking can kill the microorganisms, it doesn’t destroy the mycotoxins. Eating mycotoxins can cause problems ranging from hallucinations to vomiting and diarrhea to cancer or death. Some of the common mycotoxins found in grain include aflatoxins, deoxynivalenol, ochratoxin A and fumonisin B.

It might be best to leave that moldy bread alone.

It might be best to leave that moldy bread alone.Yulia Naumenko/Moment via Getty Images

The oldest known case of mycotoxin poisoning is recorded as a disease called ergotism. Ergotism was mentioned in the Old Testament and has been reported in Western Europe since A.D. 800. It has even been suggested that the Salem witch trials were caused by an outbreak of ergotism that led its victims to hallucinate, though many have disputed this idea. Wheat is less likely than other grains to have dangerous mycotoxins, which is why some have proposed that declining mortality in 18th-century Europe, especially in England, was due to the switch from a rye-based diet to a wheat-based diet.

Ultimately, you don’t need to worry about eating those pancakes. Farmers use many techniques to minimize fungal growth and remove moldy grain, and the government keeps a close eye on mycotoxin levels during crop production and storage. Just make sure you cook your bakery products before eating, and don’t eat anything that has started to mold.

Sheryl Barringer, Professor of Food Science and Technology, The Ohio State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.