New autism early detection technique analyzes how children scan faces

Mathematics researchers have developed a technique for detecting autism based on how toddlers’ eyes scan the features of faces, that could eventually make a diagnostic process faster and less stressful for children and families.

Imagine that your son Tommy is about to turn two. He is a shy and sweet little boy, but his behaviours can be unpredictable. He throws the worst temper tantrums, sometimes crying and screaming inconsolably for an hour. The smallest changes in routines can throw him off.

Is this a bad case of the so-called “terrible twos”? Should you give Tommy some time to grow out of this phase? Or, are these signs of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) — the neurodevelopmental disorder that affects around two per cent of the population, the equivalent of

about one or two children on a full school bus? And how will you find out?

Our research group at the Applied Mathematics Department at University of Waterloo has developed a new ASD detection technique that distinguishes different eye-gaze patterns to help doctors more quickly and accurately detect ASD in children.

We did this because there are so many benefits of early ASD diagnosis and intervention. Studies have found that interventions implemented before age four are associated with significant gains in cognition, language and adaptive behaviour. Similarly, researchers have linked the implementation of early interventions in ASD with improvements in daily living skills and social behaviour. Conversely, late diagnosis is associated with increased parental stress and delays early intervention, which is critical to positive outcomes over time.

Current ASD interventions

Symptoms of ASD typically appear in the first two years of life and affect the child’s ability to function socially. Although current treatments vary, most interventions focus on managing behaviour and improving social and communication skills. Because the capacity for change is greater the younger the child is, one can expect the best outcomes if diagnosis and intervention are made early in life.

Assessment of ASD includes a medical and neurological examination, an in-depth questionnaire about the child’s family history, behaviour and development or an evaluation from a psychologist.

Unfortunately, these diagnostic approaches are not really toddler-friendly and can be expensive. One can imagine that it is much easier for children to just look at something, like the animated face of a dog, than to answer questions in a questionnaire or be evaluated by a psychologist.

Mathematics as new microscope

You might wonder: What do mathematicians have to do with autism detection?

This is indeed an example of interdisciplinary research our group is involved in. We use mathematics as a microscope to understand biology and medicine. We build computer models to simulate the effects of various drugs and we apply mathematical techniques to analyze clinical data.

We believe that mathematics can objectively distinguish between behaviours of children with ASD from their neurotypical counterparts.

We know that individuals with ASD visually explore and scan a person’s face differently from neurotypical individuals. In developing the new technique for detecting eye-gaze patterns, we evaluated 40 children, mostly four- or five-year-olds. About half of these children are neurotypical, whereas others have ASD. Each participant was shown 44 photographs of faces on a screen, integrated into an eye-tracking system.

The infrared device interpreted and identified the locations on the stimuli at which each child was looking via emission and reflection of wave from the iris.

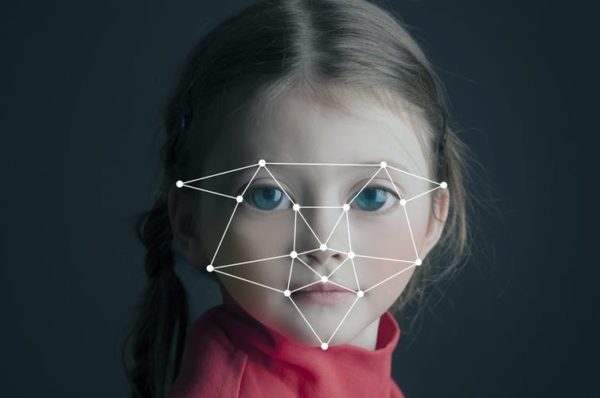

When looking at a person’s face, a neurotypical child focuses more on the eyes whereas a child with ASD focuses more on the mouth.

When looking at a person’s face, a neurotypical child focuses more on the eyes whereas a child with ASD focuses more on the mouth.(Shutterstock)

Patterns of eye movement

The images were separated into seven key areas — which we named features — in which participants focused their gaze: under the right eye, right eye, under the left eye, left eye, nose, mouth and other parts of the screen. We used four different concepts from network analysis to evaluate the varying degree of importance children placed on these features.

Not only did we want to know how much time the participants spent looking at each feature, we also wanted to know how they moved their eyes and scanned the faces.

For instance, researchers have known that when looking at a person’s face, a neurotypical child focuses more on the eyes whereas a child with ASD focuses more on the mouth. Furthermore, a child with ASD also scans faces differently. When moving their focus from someone’s eyes to their chin, for example, a neurotypical child likely moves their eyes more quickly, and via a different path than would a child with ASD.

Child-friendly diagnostic process

While it is not yet possible to enter a doctor’s office and request this test, our hope is that this research may eventually make the diagnostic process less stressful for children.

To use this technology would require an infrared eye-tracker, which is commercially available, plus our network analysis technique. We have explained the algorithms so any software developers who wanted to could, theoretically, implement them.

By removing some of the barriers to early diagnosis, we hope that more children with ASD can receive early intervention, resulting in improved quality of life and more independence in the long term.

[ You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter. ]

Anita Layton, Canada 150 Research Chair in Mathematical Biology and Medicine; Professor of Applied Mathematics, Pharmacy, and Biology, University of Waterloo y Mehrshad Sadria, M. Math Candidate, Applied Mathematics Department, University of Waterloo

Este artículo fue publicado originalmente en The Conversation. Lea el original. Photo: Shutterstock