How Sears helped make women, immigrants and people of color feel more like Americans

Sears did more than pioneer the mail-order catalog over a century ago. The iconic retailer helped make America a more inclusive place at a time when Jim Crow was rampant and women couldn’t even vote.

The news that Sears had filed for bankruptcy is a reminder of this history and the important role it played in changing the very fabric of American society.

Indeed, while it’s only the latest in a growing list of retail institutions that have gone under in recent years, Sears’s demise feels different to me – a U.S. historian who focuses on how consumer culture shapes gender and racial identities.

More than any of its other competitors, Sears – and its mail-order catalog – helped usher in the current culture of consumerism, which played an important role in making women, immigrants and people of color feel part of American life.

Changing the way we shop

The Oct. 15 announcement that Sears – founded in 1893 by Richard Warren Sears and Alvah Curtis Roebuck – filed for bankruptcy did not come as a surprise. After all, the company, which began as a mail-order catalog and later developed into a department store chain, had been struggling for years.

For younger Americans – accustomed to shopping on the internet with a couple of clicks and getting virtually anything they like in a box at their doorstep within a day or two – the news of Sears closing might not seem like a big deal. The image of customers cramming downtown streets on their shopping sprees or the excitement of receiving the season’s catalog in the mail is foreign to them.

Yet, in the late 19th century, as department stores and trade catalogs like Sears began appearing on the American landscape, they changed not only how people consumed things but culture and society as well. At the same time, consumption was starting to become crucial to Americans’ understanding of their identity and status as citizens.

In particular, for marginalized groups such as women, African-Americans and immigrants, who were often barred from positions of power, consumer culture gave them a way to participate in American politics, to challenge gender, race and class inequalities, and to fight for social justice.

AP Photo/File

Opening doors to women

The establishment of the department store in the mid-19th century facilitated the easy consumption of ready-made goods. And because consumption was primarily associated with women, it played an important role in shifting gender norms.

More specifically, department stores disrupted the Victorian “separate spheres” ideology that kept women out of public life. The new stores allowed them to use their position as consumers to claim more freedoms outside of the home.

The first department stores catered to these middle-class women and were very much dependent on their dollars. They were built as “semi-private” spaces in which women could enjoy shopping, eating and socializing without transgressing sexual respectability norms – yet providing women with the opportunity to expand “the domestic sphere” into the city.

The clustering of these retail establishments gave rise to new shopping districts, which recreated urban centers as welcoming spaces for women. Instead of the dirty, dangerous and hostile places downtowns once were, department stores facilitated the construction of safe and clean sidewalks, well-lit areas and big window displays that attracted women into the stores.

In the process, these department stores also legitimized women’s presence in downtown streets, enabling them to claim more than just their right to shop. Women used their power as consumers in their fight for suffrage and political rights, using the shopping windows of department stores to advertise their cause and to draw public support.

Horseshoes, gramophones and dresses for all

But not all shoppers shared in these new “freedoms” equally.

Department stores mainly welcomed middle-class white shoppers. Barriers of race and class prevented working-class women or nonwhite women from participating fully in commercial life.

Yet, if the tangible space of the store proved to be exclusive, the mail-order catalog – a marketing method that Sears perfected and became most famous for – offered a more inclusive vision of American democracy.

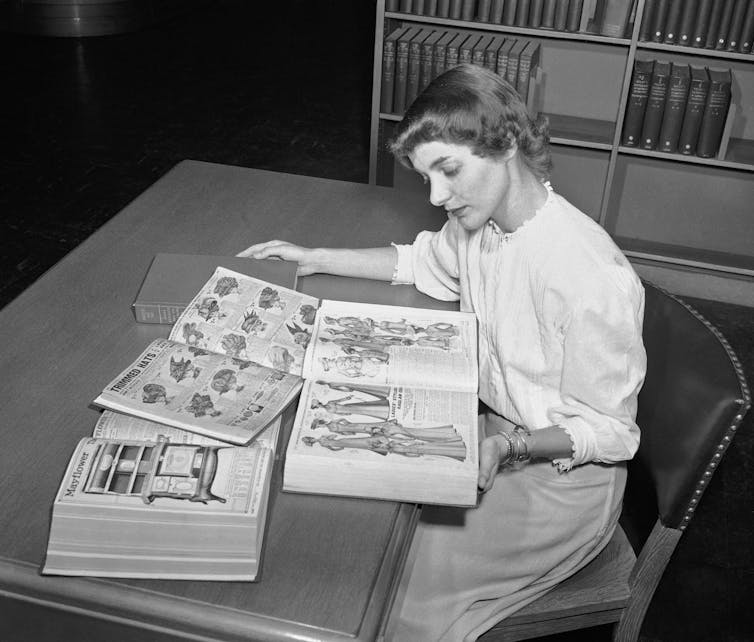

AP Photo/Edward Kitch

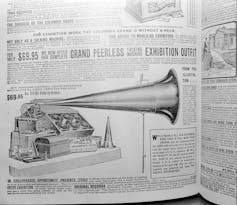

Beginning in 1896, after Congress passed the Rural Free Delivery Act, Sears catalogs reached all across the country, offering everything from a dress and a drill to a horseshoe and a gramophone, all at prices many could afford. The colorful illustrated catalogs were especially attractive to rural consumers, who despite many of them not knowing how to read could still participate by looking at the pictures.

Taking advantage of the ready-made revolution, Sears catalogs offered women from different classes, races and regions the possibility to dress like the fashionable women in Paris or New York, turning consumption into an agent of modernity as well as of democracy.

For immigrant women, the “American Styles” sold at Sears enabled them to shed their “foreignness” and appear as an American with all the privileges of citizenship.

For blacks in the Jim Crow South, Sears catalogs were also a way to claim citizenship and challenge racism. As scholars have shown, buying from a mail-order catalog allowed African-Americans to assert their right to participate as equals in the market, turning the act of shopping via the mail into a political act of resistance.

In a period when many department stores did not welcome African-American consumers, or discriminated against them, mail-order catalogs like those offered by Sears proved to be the easiest way to avoid such obstacles. These catalogs functioned also as a fantasy literature, through which one could participate, if only by imagination, in the mainstream consumer culture as equal.

AP Photo/Charles Bennett

Will Americans still have a shared consumer identity?

The success of Sears catalogs in reaching across diverse populations created a common shopping experience and eventually a common identity around which all Americans could be united.

Through its catalog and consumer culture, Americans from all walks of life – rural and urban, men and women, white and black, poor and rich – could dress the same, eat the same and even live in similar mail-order houses. And it was through consumption, arguably, that they could think of themselves as Americans.

Today, as the internet offers us “one-of-a-kind” items and a personalized shopping experience unlike any other, Sears won’t be around to offer us this shared identity. In other words, the democratic power of consumption is changing alongside that of the retail landscape.

The end of Sears and other institutions that created a shared consumption leads me to wonder whether consumer culture will continue to define our society and our democracy. And if so, how.

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox, Visiting Assistant Professor, Case Western Reserve University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. Photo: Shutterstock