Goodbye Kepler, hello TESS: Passing the baton in the search for distant planets

For centuries, human beings have wondered about the possibility of other Earths orbiting distant stars. Perhaps some of these alien worlds would harbor strange forms of life or have unique and telling histories or futures. But it was only in 1995 that astronomers spotted the first planets orbiting sunlike stars outside of our solar system.

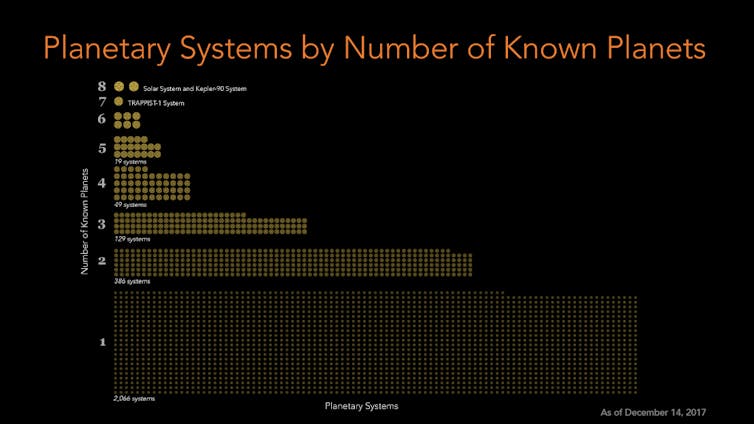

In the last decade, in particular, the number of planets known to orbit distant stars grew from under 100 to well over 2,000, with another 2,000 likely planets awaiting confirmation. Most of these new discoveries are due to a single endeavor — NASA’s Kepler mission.

NASA/Ames Research Center/Wendy Stenzel and The University of Texas at Austin/Andrew Vanderburg, CC BY

NASA Ames, CC BY

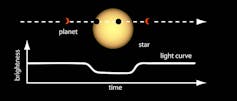

Kepler is a spacecraft housing a 1-meter telescope that illuminates a 95 megapixel digital camera the size of a cookie sheet. The instrument detected tiny variations in the brightness of 150,000 distant stars, looking for the telltale sign of a planet blocking a portion of the starlight as it transits across the telescope’s line of sight. It’s so sensitive that it could detect a fly buzzing around a single streetlight in Chicago from an orbit above the Earth. It can see stars shake and vibrate; it can see starspots and flares; and, in favorable situations, it can see planets as small as the moon.

Kepler’s thousands of discoveries revolutionized our understanding of planets and planetary systems. Now, however, the spacecraft has run out of its hydrazine fuel and officially entered retirement. Luckily for planet hunters, NASA’s TESS mission launched in April and will take over the exoplanet search.

NASA/Tim Jacobs, CC BY

Kepler’s history

The Kepler mission was conceived in the early 1980s by NASA scientist Bill Borucki, with later help from David Koch. At the time, there were no known planets outside of the solar system. Kepler was eventually assembled in the 2000s and launched in March of 2009. I joined the Kepler Science Team in 2008 (as a wide-eyed rookie), eventually co-chairing the group studying the motions of the planets with Jack Lissauer.

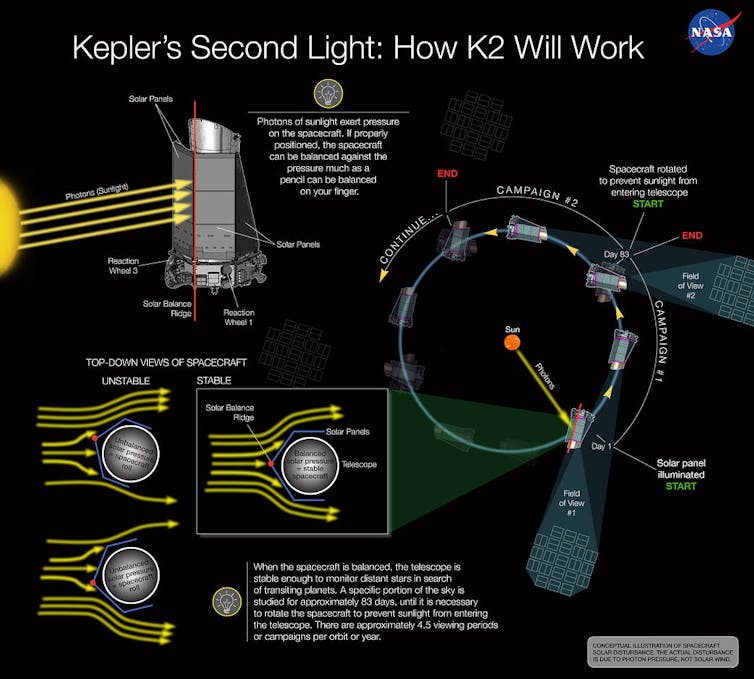

Originally, the mission was planned to last for three and a half years with possible extensions for as long as the fuel, or the camera, or the spacecraft lasted. As time passed, portions of the camera began to fail but the mission has persisted. However, in 2013 when two of its four stabilizing gyros (technically “reaction wheels”) stopped, the original Kepler mission effectively ended.

NASA Ames/W Stenzel, CC BY

Even then, with some ingenuity, NASA was able to use reflected light from the Sun to help steer the spacecraft. The mission was rechristened as K2 and continued finding planets for another half decade. Now, with the fuel gauge near empty, the business of planet hunting is winding down and the spacecraft will be left adrift in the solar system. The final catalog of planet candidates from the original mission was completed late last year and the last observations of K2 are wrapping up.

Kepler’s science

Squeezing what knowledge we can from those data will continue for years to come, but what we’ve seen thus far has amazed scientists across the globe.

We have seen some planets that orbit their host stars in only a few hours and are so hot that the surface rock vaporizes and trails behind the planet like a comet tail. Other systems have planets so close together that if you were to stand on the surface of one, the second planet would appear larger than 10 full moons. One system is so packed with planets that eight of them are closer to their star than the Earth is to the Sun. Many have planets, and sometimes multiple planets, orbiting within the habitable zone of their host star, where liquid water may exist on their surfaces.

As with any mission, the Kepler package came with trade-offs. It needed to stare at a single part of the sky, blinking every 30 minutes, for four straight years. In order to study enough stars to make its measurements, the stars had to be quite distant – just as when you stand in the middle of a forest, there are more trees farther from you than right next to you. Distant stars are dim, and their planets are hard to study. Indeed, one challenge for astronomers who want to study the properties of Kepler planets is that Kepler itself is often the best instrument to use. High quality data from ground-based telescopes requires long observations on the largest telescopes – precious resources that limit the number of planets that can be observed.

We now know that there are at least as many planets in the galaxy as there are stars, and many of those planets are quite unlike what we have here in the solar system. Learning the characteristics and personalities of the wide variety of planets requires that astronomers investigate the ones orbiting brighter and closer stars where more instruments and more telescopes can be brought to bear.

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, CC BY

Enter TESS

NASA, CC BY

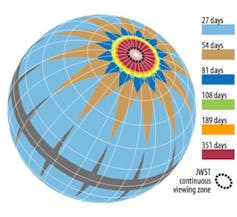

NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite mission, led by MIT’s George Ricker, is searching for planets using the same detection technique that Kepler used. TESS’ orbit, rather than being around the Sun, has a close relationship with the Moon: TESS orbits the Earth twice for each lunar orbit. TESS’ observing pattern, rather than staring at a single part of the sky, will scan nearly the entire sky with overlapping fields of view (much like the petals on a flower).

Given what we learned from Kepler, astronomers expect TESS to find thousands more planetary systems. By surveying the whole sky, we will find systems that orbit stars 10 times closer and 100 times brighter than those found by Kepler – opening up new possibilities for measuring planet masses and densities, studying their atmospheres, characterizing their host stars, and establishing the full nature of the systems in which the planets reside. This information, in turn, will tell us more about our own planet’s history, how life may have started, what fates we avoided and what other paths we could have followed.

The quest to find our place in the universe continues as Kepler finishes its leg of the journey and TESS takes the baton.

Jason Steffen, Assistant Professor of Physics and Astronomy, University of Nevada, Las Vegas

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.