As a Young Reporter, I Went Undercover to Expose the Ku Klux Klan

Spike Lee’s powerful new film, “BlacKkKlansman,” tells the true story of Ron Stallworth, an African-American police officer who infiltrates a local branch the Ku Klux Klan in 1979.

That same year, I also signed up to join the Klan. And at a secret meeting I even met the Grand Wizard himself, David Duke, the same Klan leader featured in Lee’s film.

I was a rookie Klansman at the time, and I’d been recruited to join the cause.

Sort of.

Like Stallworth, I wasn’t a true believer and had a very different agenda from the Klan’s.

The Klan descends on Connecticut

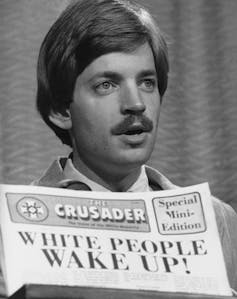

It was the fall of 1979, and I was a first-year reporter at The Hartford Courant when David Duke launched a recruiting effort in, of all places, Connecticut. His “Klan calling cards” and his newspaper, The Crusader, started appearing in factory parking lots, restaurants, high schools and college campuses.

To cover the story for the state’s largest newspaper, I was teamed with a veteran reporter named Bill Cockerham. We called Duke’s headquarters in Metairie, Louisiana.

David Duke was 29 at the time – an educated, clean-cut Klansman campaigning for a seat in the Louisiana State Senate.

AP Photo

Duke was happy to talk. He made plain his aim to recruit young people and to remake the Klan into a gentler, kinder brand of bigotry. He wasn’t anti-black or anti-Jewish, he said. “We are simply pro-white and pro-Christian.”

“It’s the white majority that are losing their rights, not the blacks or the Jews,” he insisted. “We’re the ones being attacked on the streets and they call us haters when we fight back for our rights and heritage.”

It was vintage Duke. He was trying, as one expert told us, to be “everybody’s Klansman,” using his considerable marketing skills to sugarcoat racism.

He told us his recruiting efforts had struck a chord in the Nutmeg State, claiming more than 200 new members and several hundred more associate members. While no statewide organization was in place, there were, he claimed, a number of robust, local dens. He did mention a statewide organizer, but when we requested repeatedly to speak to him, Duke balked.

The KKK was a secret organization, he explained. He couldn’t do that. But because he was the face of the organization, we could call the Metairie office any time – he’d be happy to talk Klan.

Getting access

The front-page article in The Courant appeared a few days later – “Klan Unit Attracting New Members: New Recruits Join Klan Through Mail” – and local radio and television stations pounced on the story.

Duke was suddenly a newsmaker, and the press and public struggled with the idea he could be successfully establishing a footprint in Connecticut, given that the Klan was mostly associated with the South.

Hartford Courant, Author provided

Of course, no one knew whether Duke’s numbers were accurate; the story reported his claims of a groundswell of support.

Which is why I clipped out an application from a copy of his Crusader in our newsroom, filled it out using a false identity and mailed it to Metairie along with the $25 entry fee. (The use of deception in reporting is another story altogether, a matter regularly discussed in journalism ethics courses.)

My goal was to get inside Duke’s local outfit, identify his local leader and either verify or debunk his headcount of followers. In the mail, I soon received my Klan membership card, a certificate of Klan citizenship and a Klan rule book with a picture of Duke in his fancy Grand Wizard robe telling me to buy a robe for $28. Just like that I had joined the Klan.

Then I waited. I figured it wouldn’t take long for my compatriots to reach out and bring me into the fold, where I’d get the inside story. That was the game plan, and when I occasionally called down to Duke’s office in Metairie, using my new identity, I was assured I’d be hooked up with like-minded Connecticut racists in short order.

But nothing happened. Weeks went by. Meanwhile, David Duke continued to reap regular coverage in Connecticut media, with the imperial wizard claiming huge success in his statewide recruitment.

My break came in early December 1979. Duke announced he’d decided to travel to Connecticut and to two other New England states. The trip would be a kind of climax to his fall membership drive. He would visit several Connecticut cities and speak with the press at each stop, before holding a private rally at night with his Connecticut Klansmen.

And that’s when I got the call – all hands were summoned for the secret mass meeting on Friday, Dec. 7. I was told that for security reasons the location would not be disclosed until the actual day but to be on call.

The moment of truth

Teamed again with the veteran reporter, I spent most of that Friday afternoon on the move. I was instructed to call Metairie and was directed to head west from Hartford. While Duke staged a press conference at a Waterbury motel, I waited in a local bar, where Duke’s local point person finally contacted me. He directed me to Grange hall in Danbury, which they’d rented posing as a historical group.

I left my colleague behind and was met in a rear parking lot by three “enforcers.” They asked for my Klan ID card, and then waved me through. I walked into the dimly lit room on the second floor and looked around. The hall was nearly empty, except for around two dozen men quietly mingling.

That’s when it dawned on me why I’d never heard a peep from any other Connecticut Klansmen: There was no real organization, or presence, to speak of.

While most were dressed in leather and jeans, the sandy-haired Duke wore a three-piece suit with a Klan pin on his lapel. He introduced himself to each attendee, showing off a three-ring binder with Connecticut newspaper clippings about him and the Klan.

Duke’s idea for a meeting was a simple one – a screening of D. W. Griffith’s “The Birth of a Nation,” the 1915 blockbuster about the Civil War and Reconstruction. (In Spike Lee’s movie, a Klan meeting also involves a showing of the film.)

To Griffith, a Southerner, the robed Klansmen were heroes, riding to the rescue and saving the South from the lawlessness and chaos of Reconstruction.

That night in Danbury, Duke used the film as a teaching tool, turning the darkened Grange hall into a classroom for a course on white power. Standing next to an American flag, he read aloud the film’s subtitles and then added his own bigoted commentary. When a group of Klansmen on horses dump the corpse of a black man on a front porch, Duke began to clap his hands – a firm clap that grew louder as others in the room joined in to applaud the death of a black man on screen.

Hartford Courant, Author provided

I left that meeting with the story we’d been after for months – the identity of the Connecticut leader and, more importantly, the actual numbers in Duke’s much-ballyhooed statewide Klan. It wasn’t several hundred but closer to two dozen. Duke’s run of media coverage in Connecticut dried up immediately.

We exposed Duke as the con man who’d bluffed his way into a run of free publicity to spew is pro-white nonsense – a transparently perverse message that somehow has regained currency today. The imperial wizard’s rhetoric of 1979 is parroted almost verbatim by a new generation of haters who are attracting plenty of media coverage.

I never spoke to Duke again, but I did receive a Christmas card from him that holiday season – addressed to my Klan alias, apparently mailed before the article was published.

The red card featured two Klansmen in robes holding a fiery cross. The caption read: “May you have a meaningful and merry Christmas and may they forever be White.”

Dick Lehr, Professor of Journalism, Boston University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.